Roberto Clemente (1934–1972) casts a long shadow over Pittsburgh’s past—not just as a baseball icon, but as a symbol of character, compassion, and cultural pride. So central is his legacy that the city renamed the Sixth Street Bridge in his honor, connecting downtown to the ballpark he helped make legendary.

By the time his career ended, Clemente had racked up a .317 lifetime batting average and exactly 3,000 hits—milestones that only begin to reflect his importance. Born in Carolina, Puerto Rico, Clemente wasn’t just a trailblazing athlete; he was a source of pride for Latino communities across the Americas and a force for social good. He lived by a simple yet powerful creed: “If you have a chance to help others and fail to do so, you are wasting your time on this Earth.” From sandlots in Puerto Rico to the grandstands of Forbes Field, that belief guided his every step.

Early Life and Road to the Majors

Roberto Clemente was born on August 18, 1934, in Carolina, Puerto Rico . The youngest of seven children in a working-class family, he showed prodigious athletic ability from a young age. By 17 he was starring for the Santurce Crabbers in Puerto Rico’s highly competitive Winter League . A Brooklyn Dodgers scout praised his rare talent: “Nobody could throw any better than that, and nobody could run any better than that,” he recalled . The Dodgers signed Clemente in 1952, but they tried to hide him in the minors. After the 1954 season, the Pittsburgh Pirates used the Rule 5 draft to acquire him for just $4,000 .

From 1955 on, Clemente would call Pittsburgh home. His early years with the Pirates involved growing pains: he battled injuries, homesickness and an English language barrier. But by 1960 he “came of age” as a player . That year he batted .312 with a team-high 94 RBI to lead Pittsburgh to the World Series . In the Fall Classic, Clemente hit .310 to propel the Bucs past the New York Yankees in seven games, earning his first championship ring. Over the next decade he established himself as a complete star: he won four National League batting titles, the 1966 NL Most Valuable Player Award, and a string of 12 consecutive Gold Glove Awards in right field . In 1971, at age 37, he again led Pittsburgh to a World Series victory (hitting a remarkable .414 in the Series and winning its MVP) . Late in the 1972 season, Clemente recorded his 3,000th hit – becoming only the 11th major leaguer ever to reach that plateau . By then he had a .317 career batting average , 240 home runs, 1,305 RBI and 3,000 hits – hallmarks of a rare career.

- Hitting Prowess: .317 career average; first Latin player with 3,000 hits . Four NL batting titles .

- Defensive Excellence: Twelve Gold Glove Awards in right field , tying Willie Mays’ record for outfielders.

- Accolades: 15-time All-Star (1958–1972) and 2× World Series champion (1960, 1971) .

- MVP Honors: 1966 National League MVP and 1971 World Series MVP .

- Milestones: Reached 3,000 hits in 1972 as the 11th player ever ; finished with 4,816 lifetime total bases .

These feats alone would guarantee Clemente a place in baseball lore. But to understand Clemente’s true greatness, one must also consider the era he played in and the barriers he broke down.

Battling Prejudice and Embracing Heritage

Clemente rose to stardom in an era still shadowed by segregation and prejudice. He arrived in Pittsburgh just eight years after Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color line, at a time when many cities and teams were only partially integrated . Yet as a Black Latino, Clemente faced unique challenges. In Pittsburgh and on the road, he encountered racial slurs and “ambiguous hostility,” as he put it. Sportswriters often anglicized his name, calling him “Bobby” or “Bob” instead of Roberto , and they mocked his Spanish accent in print. One reporter famously phonetically quoted him as saying “I get heet,” after hitting a double in the 1961 All-Star Game – a caricature of his broken English . This dismissive coverage betrayed a larger pattern of bias: injuries Clemente suffered were sometimes portrayed as excuses, while a white player battling similar ailments was hailed as a hero . As Clemente himself noted:

“Mickey Mantle is God,” he observed, “but if a Latin or black is sick, they say it is in his head.”

Clemente refused to let such prejudice dim his spirit or silence his identity. He was proud of his Puerto Rican and Afro-Caribbean heritage and insisted on being called Roberto. Chicago White Sox manager Ozzie Guillén later summarized Clemente’s role for Latinos: “He is the Jackie Robinson of Latin baseball…He was a man who was happy to be not only Puerto Rican, but Latin American” . Historian Doris Kearns Goodwin echoed this, saying “there was a largeness to Clemente’s persona that transcended baseball” .

Even as he endured insults, Clemente let his play do the talking. He showed humility and unselfishness; teammates and competitors lauded him as a “fighter” who constantly played through pain to help his team . Pittsburgh fans came to revere him as one of their own, and he became a symbol of hope for the city’s growing Latino community. (On September 1, 1971, for example, Pittsburgh became the first MLB team to start an all-Black/Latino lineup, featuring Clemente and fellow Hall of Famers, an emblem of changing times.)

Off-Field Humanitarianism and Activism

Clemente’s devotion extended far beyond the playing field. He believed deeply in giving back – especially to the poor and disenfranchised in Latin America and the Caribbean. “If you have a chance to help others and fail to do so, you are wasting your time on this Earth,” he often said . Throughout his career he lived by that creed. Off-seasons found him organizing baseball clinics and charity drives in Puerto Rico, Cuba, Nicaragua and elsewhere. He routinely visited children in hospitals and delivered toys, food, and medical supplies to needy families. In winter of 1963–64 he played in Nicaragua’s winter league and became a beloved figure there . He vowed to return whenever he could.

Clemente also lent his voice to social causes. He supported the fledgling Major League Baseball Players Association, serving as the Pirates’ union representative. A close ally of longtime union leader Marvin Miller, Clemente championed players’ rights and fought the reserve clause that kept players tied to one team . He invited activists like Curt Flood (who challenged baseball’s reserve clause in court) to union meetings in Puerto Rico to drum up support .

Closer to home, Clemente was passionate about youth and community development. He helped start a “Sports City” project in Puerto Rico to provide athletics and education for inner-city kids . He campaigned against drug use and gang violence, often saying that baseball was a way to inspire young people to a better life. In Pittsburgh he quietly supported local charities and made frequent appearances at community events.

These actions were not for public glory. “He played a kind of baseball that none of us had ever seen before…as if it were a form of punishment for everyone else on the field,” wrote author Roger Angell, highlighting his excellence . But Angell might have been speaking just as much about Clemente’s character as his skill. By 1972, the poster-boy athlete from Puerto Rico had become a beloved global figure for his compassion and selflessness.

Final Mission and Tragic Death

Clemente’s greatest act of heroism came in his final days. On December 23, 1972, a magnitude-6.3 earthquake devastated Managua, Nicaragua. Clemente immediately began collecting relief supplies in Puerto Rico, determined to help the victims. But he was soon outraged to learn that much of the aid was being stolen by Nicaragua’s corrupt Somoza regime – locking it in warehouses instead of delivering it to those in need . Refusing to let bureaucracy and banditry thwart him, he arranged to personally fly the next shipment of supplies to Managua.

On New Year’s Eve 1972, at age 38, Clemente boarded a chartered DC-7 plane bound for Nicaragua, loaded with medicine, food, and clothing. Also on board were his friend and associate Angel Lozano, the plane’s pilots, and flight engineer. Seconds after takeoff from San Juan, Puerto Rico, the overloaded plane went down in the Atlantic Ocean . Investigators concluded it likely had too much weight and suffered mechanical problems. No one survived, and Clemente’s body was never recovered .

The news stunned Pittsburgh, Puerto Rico, and the sports world. Fans and teammates mourned the loss of their star, but his death also enshrined him as more than an athlete. “Baseball survives,” wrote columnist Jimmy Cannon of the New York Journal-American, “because guys like Clemente still play it” . Clemente became a martyr for humanitarianism – “the first martyr in the sports world,” as one observer put it – whose final act embodied the values he had championed.

Legacy in Pittsburgh and Beyond

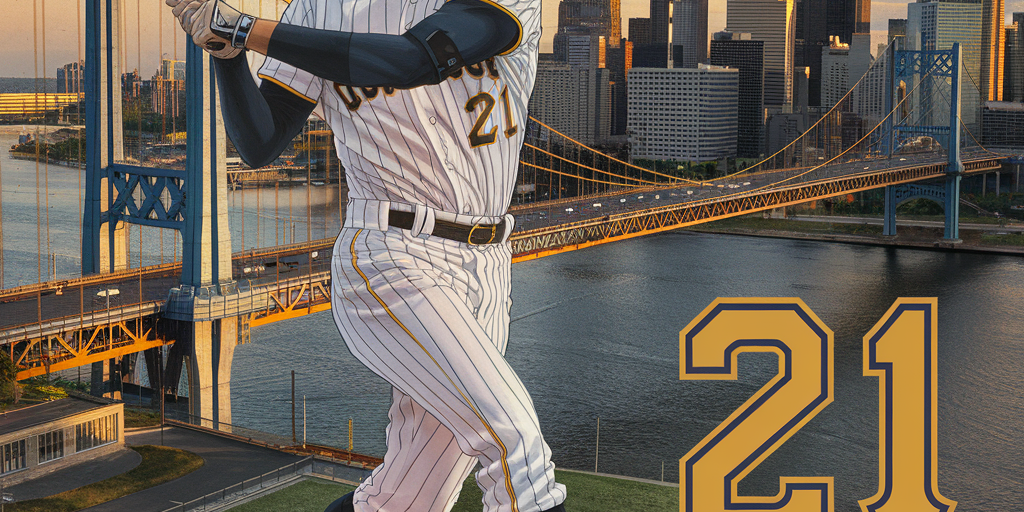

Pittsburgh’s “favorite son” received an outpouring of tributes. In 1973 the Baseball Writers waived the usual five-year waiting rule to elect Clemente to the Hall of Fame, making him the first Latin American-born player so honored. The Pirates retired his number 21 and wore a black armband in 1973 in his memory. In 1998 the city officially renamed the Sixth Street Bridge the Roberto Clemente Bridge; today it is often festooned in Pirate black-and-gold and serves as a grand promenade from downtown to PNC Park. A bronze statue of Clemente stands on Federal Street outside PNC Park, just steps from the bridge. Dedicated in 1994 during All-Star Week (and moved from the old Three Rivers Stadium), the statue depicts Clemente mid-swing and rests on a pedestal containing soil from Puerto Rico and Forbes Field — symbolically linking his Puerto Rican roots with his Pittsburgh legacy.

Just beyond the right-field wall of PNC Park lies Roberto Clemente Memorial Park, maintained by the city’s Parks and Recreation. This riverside park features a 21-foot granite “Tribute Wall,” cascading fountains (which children wade through on hot days), and a bronze relief of Clemente in action . Nearby, the street that once led to Forbes Field was renamed Roberto Clemente Drive . In all these ways, the city’s landscape keeps his memory alive.

Baseball at large also honors Clemente each year. MLB celebrates Roberto Clemente Day every September (around his Aug 18 birthday) to recognize his legacy. On that day each year the Roberto Clemente Award is announced: it is given to a player who best exemplifies Clemente’s character and community involvement . (Originally created in 1971 as the Commissioner’s Award, it was renamed for Clemente after his death .) Each team nominates one player; past winners include stars like Tony Gwynn, Derek Jeter, and Curt Schilling – players who not only excel on the field but also do extraordinary charity work in the spirit of Clemente .

Finally, Clemente’s impact echoes far beyond Pittsburgh. He inspired countless Latin American athletes. To this day he is regarded as el ídolo boricua (the Puerto Rican idol). Puerto Rico has named cities, parks, and baseball fields after him (including the Roberto Clemente Coliseum in San Juan), and his face adorns murals on Caribbean streets. On August 6, 1973, Clemente became the first player from Latin America inducted into the Hall of Fame , a milestone noted by fans across the hemisphere. As Ozzie Guillén put it, Clemente proved “a Latin American player could make it that big in the big leagues” . In fact, one Nicaraguan fan in 2022 remarked that Clemente taught people in his country “to believe in human decency, not just talent” after so many idols fell short . His legend endures in inspiration: baseball managers still call on his name when urging players to play selflessly, and writers cite his life as a benchmark for character.

Roberto Clemente’s story reminds us that true greatness isn’t measured only in home runs or championships. It’s measured by the lives we touch and the causes we serve. In an era of cynicism, he remains a luminous example of how an athlete can use his platform for good. As the Hall of Fame notes, Clemente’s “greatness was not just limited to the baseball diamond.” He once said, “If you have a chance to accomplish something that will make things better for people coming behind you and you don’t do that, you are wasting your time on this Earth.” Roberto Clemente lived by those words to the end. In that sense, his time on Earth was anything but wasted.