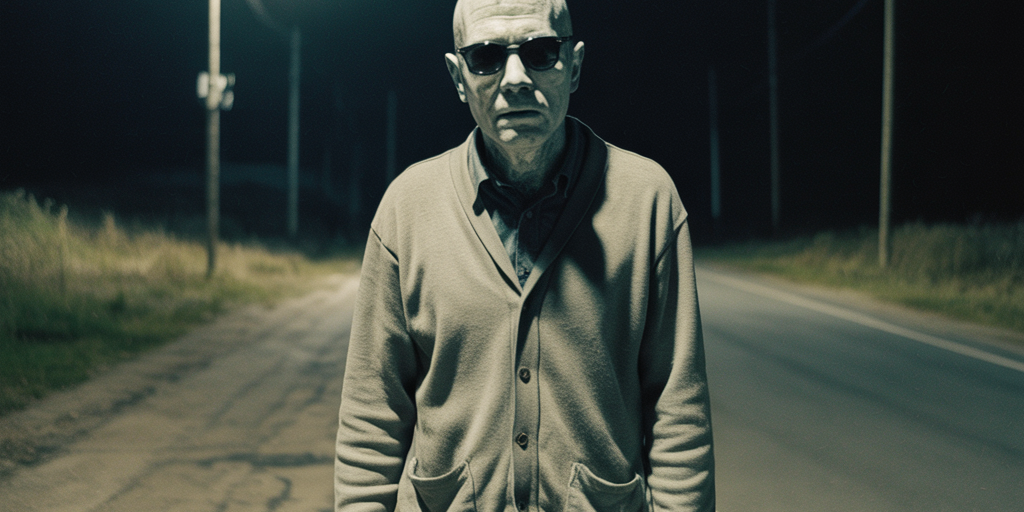

Charlie No Face was Raymond Robinson, a real man from western Pennsylvania who survived a childhood electrical accident. His nighttime walks inspired the Green Man legend. On a moonless summer night in western Pennsylvania decades ago, a group of teenagers parks on the side of a lonely country road. They kill the engine and nervously honk the horn three times, daring a local legend to emerge from the darkness. According to the story they have heard since childhood, a glowing green ghost, a faceless man, wanders these back roads, haunting anyone who crosses his path. The teens laugh uneasily, half certain nothing will happen. But deep down, each wonders: What if Charlie No Face is real?

It turns out he was real, just not in the way the spooky tales suggest. Charlie No Face, also known as the Green Man, was not a ghost but a flesh and blood person named Raymond Robinson. Far from a vengeful spirit, he was a gentle, ordinary man who endured an extraordinary tragedy. Over time, Raymond’s true story was distorted and exaggerated into one of Pittsburgh’s most persistent urban legends. In this article, we will peel back the layers of myth and share the real history of Charlie No Face: the childhood accident that changed his life, the midnight walks that made him a legend, and how Pittsburgh’s fascination turned a kind, lonely man into a local folk tale.

Key Facts

- Real name Raymond Robinson

- Also known as Charlie No Face, the Green Man

- Where Western Pennsylvania especially Beaver County near Koppel and Frisco

- Era Mid twentieth century evening and late night walks

- Origin Childhood electrical accident that caused severe facial injuries

- What is true He was a real person who preferred to walk at night to avoid attention

- What is legend Glowing green skin, haunting a tunnel, chasing cars

- Respect Robinson faced cruelty as well as kindness. Please discuss the story with care

- Safety note Do not trespass at tunnels or on private roads

The Legend of the Green Man

Walk into any Pittsburgh-area diner or bar and ask about Charlie No-Face, and you’re bound to hear a shiver-inducing story. In fact, ask ten different locals and you might hear ten different versions. Some will swear he was the ghost of a utility worker killed by a live wire. Others insist he was a factory worker who fell into a vat of acid, or a man struck by lightning who now stalks the backroads . His ghostly domain also shifts with the storyteller: one might place him on a deserted industrial road near New Castle, another in an old tunnel in South Park, or lurking along State Route 351 between Koppel and Big Beaver where many firsthand “sightings” occurred .

All the tales agree on one point – the Green Man’s ghastly appearance. In whispers, people describe a man with no face, his features melted away, sometimes with a hint of eerie green glowing skin. According to legend, if you’re brave enough to drive into his territory at night and perform a ritual (perhaps blinking your car lights or honking three times), the Green Man will appear to frighten (or even chase) you away . Generations of Pittsburgh teenagers have treated late-night drives to find Charlie No-Face as a rite of passage, a test of courage akin to summoning Bloody Mary in a mirror . They call these “legend trips” – thrill-seeking excursions fueled by spooky lore.

What’s remarkable is how far and wide the legend spread. By the 1960s and ’70s, stories of the faceless Green Man had traveled well beyond Beaver County. Sightings were rumored not just in Beaver Falls and Big Beaver (where the real man lived) but in neighborhoods all around Pittsburgh – from the North Hills to McKees Rocks, West Mifflin to Brookline, and even over the state line into Youngstown, Ohio . The story leaped from person to person like a campfire ghost tale. Soldiers from Western Pennsylvania stationed abroad during Vietnam wrote home asking if the Green Man still roamed the roads . Well before the internet, Charlie No-Face’s fame (or infamy) spread through whispered rumors, newspaper write-ups, and the excited testimonies of those who swore they’d met the monster and lived to tell the tale.

Yet amid all the sensational variations of the myth, one version is rarely heard: the true story. As one local writer noted, the real Charlie No-Face was actually “one of the kindest human beings on the face of this earth, despite his horrible disfigurement” – a fact shared by those who knew him, but nearly lost under “decades of hyperbole” . To understand how a friendly, injured man became an immortal boogeyman, we have to go back over 100 years, to the event that started it all.

Raymond Robinson: The Man Behind the Myth

Before he was a phantom in the Pittsburgh night, Charlie No-Face was a boy named Raymond Theodore Robinson, born on October 29, 1910, in Beaver County, Pennsylvania . Raymond’s early childhood was unremarkable for its time. He grew up on the outskirts of Beaver Falls in a large blended family – one of at least seven children in a household formed after his widowed mother remarried her brother-in-law . Neighbors later remembered Raymond (or “Ray”) as a typical kid: he loved swimming in the Beaver River during summers and roaming with friends around the local Morado neighborhood on little adventures . Like many young boys, he wasn’t afraid of dares – a trait that would soon alter the course of his life.

By June of 1919, 8-year-old Raymond had already known tragedy; his father had died two years earlier in 1917 . Still, nothing could foreshadow the bizarre accident that befell him on the evening of June 18, 1919. That night, Ray and a few neighborhood friends set out to hike to a favorite swimming hole on the Beaver River, a ritual to cool off on a warm day . Their route took them across an old trolley trestle bridge that spanned a stream called Wallace Run, near the Morado section of Beaver Falls . This bridge carried tracks and electrical lines for the Pittsburgh, Harmony, Butler and New Castle Railway Company, often called the Harmony Line, an interurban trolley that once connected towns throughout the region .

The wooden trestle bridge had an eerie notoriety among local kids – just the year before, another boy had been badly electrocuted there. In September 1918, a 12-year-old boy named Robert Littell was killed by touching the high-voltage lines while playing on the same bridge . Ray and his pals knew about the fatal accident; one friend reportedly protested when Ray showed interest in climbing up to investigate something on the bridge, recalling that “a little fellow was nearly killed up there six months ago” . But youthful curiosity got the better of Raymond when the boys spotted a bird’s nest perched high atop the bridge structure. Determined to peek inside, Ray declared, “Well, I will find out,” and began to climb despite the danger .

What happened next would become the core of the Charlie No-Face legend. Ray either climbed a girder or stood on a makeshift box (accounts differ) and accidentally touched the line carrying electricity to the trolley . In an instant, 1,200 volts of direct current (and possibly a 22,000-volt transmission line above it) surged through his small body . The shock violently threw Ray from the bridge. His friends could only watch in horror as their companion was severely electrocuted and fell to the ground.

Newspaper headlines the next day were grim and dramatic. One local paper, the Beaver Falls Evening Tribune, ran the headline: “Morado Lad, 8, Shocked By Live Wire, Will Die,” reflecting the doctors’ dire prognosis . Indeed, Ray’s injuries were almost unimaginable. The electric current had obliterated his face – it was said to look “as if it had been melted with a blow torch” . He lost his eyes completely and his nose, and was left with just bits of misshapen lips and ears. One of his arms (sources indicate it was his left arm) was burned off at the elbow, essentially blown away by the jolt . His entire upper body was scorched and scarred. The fact that Ray was still alive at all was nothing short of a miracle, and for a long while, it was touch-and-go.

Surviving the Unthinkable

Against all expectations, Raymond Robinson survived his catastrophic injuries. For weeks after the accident in June 1919, local newspapers printed updates as the boy hovered between life and death in Providence Hospital in Beaver Falls . After a month, to everyone’s astonishment, Ray pulled through. Doctors openly marveled at his recovery, calling it miraculous . An August 1919 update noted, “Yet, in spite of all his affliction, the boy is in good humor,” highlighting Ray’s remarkable resilience and positive spirit even in the face of such trauma .

Still, the road ahead was not easy. Young Raymond spent much of the next few years in hospitals in Pittsburgh, undergoing multiple surgeries in hopes of improving his condition . Unfortunately, medical science of the 1920s could do little to reconstruct his face or fully restore use of his remaining arm. Ray emerged with a prosthetic nose – a simple artificial piece that he would attach to a pair of dark glasses – and later a prosthetic arm . These measures made him a bit more presentable in public, but there was no hiding the severity of his disfigurement. For the rest of his life, he would wear those tinted glasses and a cap pulled low, both to shield his face and perhaps to spare others a shock.

Back home in Beaver County, Ray’s family rallied around him. He went to live with relatives in the small town of Koppel, PA, north of Beaver Falls . His mother Louise and stepfather did their best to give Ray an ordinary life within the confines of home. They didn’t talk much about how he looked – as one nephew later explained, to them, “Uncle Ray was Uncle Ray, and that was that.” The family accepted his appearance as a reality that couldn’t be changed, and Ray himself never complained or wanted anyone’s pity . In an era when people with severe disabilities were often hidden away, the Robinsons’ matter-of-fact attitude was compassionate. (Some accounts suggest Ray’s family did keep him somewhat isolated for his own sake – for instance, a researcher found that the family ate meals separately from him, perhaps to avoid awkward stares or because Ray’s injuries made eating messy. But by all accounts, they cared for him deeply and he was not mistreated.)

Determined to stay busy and self-sufficient, Ray learned to adapt in creative ways. He taught himself Braille to read with his fingertips , and took up simple handicrafts to pass the time. Using what mobility he had, he made doormats by weaving together strips of old rubber tires, and crafted leather wallets and belts which family members would help him sell . He also had a whimsical collection of metal puzzles made from horseshoes and scrap hardware that he could deftly solve and reassemble, amazing his young nieces and nephews . These hobbies kept his hands busy and likely brought him a sense of accomplishment.

One of Ray’s greatest joys was the radio. Blinded and unable to enjoy visual pastimes, he became an avid listener of baseball games and music. Family members recall how he kept a shortwave radio in his bedroom and an old Philco radio next to his favorite easy chair in the living room . For hours he would sit there tuning into Pirates baseball broadcasts, memorizing player statistics and savoring each crack of the bat via the airwaves . In fact, Ray became something of a walking sports almanac – he astonished visitors with detailed baseball stats committed to memory, a testament to how closely he followed the game . Sports gave him an emotional escape from his isolation, allowing him to participate in Pittsburgh’s favorite pastime even if only as a listener.

Despite his significant disabilities, Ray retained a measure of physical independence. He helped with chores where he could – one memorable image is of Ray pushing an old-fashioned manual lawnmower across the yard. He couldn’t see the patches he missed, but he relished just being outside doing something useful, and his family lovingly went back over the spots he missed without fuss . He also never lost his boyhood love of nature. Ray would go hiking in the woods around the family property, feeling his way with a walking stick. He developed a clever method to navigate: he’d keep one foot on a cleared path and one foot on the brush or grass off the path, so he could sense the trail’s edge with every step . In this way he could explore familiar trails confidently. For a man who had lost so much, these small freedoms – radio, crafts, backyard chores, woodland walks – were vitally important. They kept the spark of normal life alive for Ray and showed his incredible adaptability and spirit.

Yet, even as Raymond Robinson adjusted to his “new normal,” the outside world remained less kind. Neighbors in Koppel and Big Beaver certainly knew of Ray and understood his condition. They largely left him in peace, having grown used to the sight of the disfigured man in dark glasses puttering in his yard . But beyond his immediate community, few people were aware of Raymond’s story in the 1920s and ’30s. That would change once Ray decided to step out of the shadows – literally – and into the night.

Nightly Walks on State Route 351

Around the late 1930s or early 1940s, as Ray entered adulthood, he began a habit that would ultimately make him legend. He took to walking alone at night – long, solitary strolls down the quiet country roads near his home . Exactly when and why this started is a bit of family lore. Ray’s nephew recalled that it began after a coal company strip-mined the land behind their house, destroying the familiar wooded paths Ray used to hike . With his beloved trails gone and cooped up inside all day, Ray likely yearned for another way to stretch his legs. So he turned to the paved roadways under cover of darkness.

Every few nights, once the sun had fully set, Ray would grab his walking stick around 10 PM and venture out onto Koppel-New Galilee Road, which is part of Route 351 running through rural Beaver County . He typically chose clear nights and would walk for miles, sometimes staying out past midnight before coming home . The darkness offered him safety in more ways than one. Of course, bright daylight was hard on Ray’s damaged eyes (even though he was blind, his face wounds were sensitive), but more importantly, he knew his appearance could startle or panic strangers. By walking at night on sparsely traveled roads, Ray could get exercise and freedom without drawing as much attention or causing distress .

At first, these nocturnal wanderings were a private ritual – likely unknown outside his family and close neighbors. Ray’s mother and stepfather, however, were distraught and worried each time he went out. His mother Louise would plead, “Why do you have to go?” but Ray was an adult and this was something he needed for himself . The family’s concern wasn’t unfounded. The roads could be dangerous for a blind pedestrian. On the occasions Ray stayed out very late or all night, his frantic relatives would form search parties in the middle of the night, walking up and down Route 351 with flashlights, calling his name, praying they wouldn’t find him hurt (or worse) on the roadside .

Those fears came true more than once. Ray was, sadly, struck by cars several times during his years of walking . On one occasion in the 1960s, he was hit by a car and badly injured, prompting doctors to temporarily advise him to stay in a hospital; but before long he insisted on going home to continue his quiet life . In another incident, Ray accepted a ride from some people only to have them rob him and push him out of the car, leaving him injured by the roadside. Despite these cruel setbacks, he refused to give up his walks . They were his joy and his escape, and probably one of the few times he could feel a degree of independence in the outside world.

Ironically, it was these very midnight strolls – meant to keep a low profile – that lit the spark of the legend. As the years went on, residents of Big Beaver, Koppel, and nearby towns occasionally spotted a lone figure in the darkness along the highway. Drivers would see the tap-tap of his cane or catch the reflection of their headlights in Ray’s glasses and realize someone was walking the road at night. Initially, it might have been just a local curiosity: “There’s a strange man out on the highway after dark.” But word began to spread, especially among local teenagers, that “the faceless man” was out there and could be encountered if you went looking.

Curious Visitors and the Birth of “Charlie No-Face”

By the 1940s and certainly into the 1950s, local youth culture had latched onto Ray’s nightly excursions as a source of intrigue and adventure. Teenagers with cars (or access to a family car) would pile in and cruise the quiet stretch of Route 351 hoping to catch a glimpse of the mysterious walker . Imagine the scene: a group of high school kids, windows down, inching along the country road in the dark, hearts pounding with anticipation. For many, it started as a dare or a way to kill boredom on a summer evening – Beaver County didn’t offer a lot of entertainment on Friday nights after the football games ended, so why not go “see if we can find that guy”?

At first, these encounters were ad hoc; a carload of local teens might slowly cruise and, if lucky, spot Ray tapping his way along the shoulder. Over time, however, it almost became a ritual. Young people from all over Western PA (and even beyond) would specifically drive out to Big Beaver in hopes of meeting the “faceless man.” Some came from as far as Pittsburgh’s South Hills or West Virginia, having heard wild stories through the grapevine . It was an ever-growing social phenomenon – One folklorist noted that for decades, “Going to see Charlie No-Face became a rite of passage,” as integral to local teen life as getting ice cream at Hank’s Frozen Custard, dancing at the American Legion hall, or grabbing a drink at one of Pittsburgh’s oldest bars.

During these encounters, Raymond would usually try to avoid strangers at first. Understandably shy, he often slipped into the shadows or behind trees when he heard cars approaching . But if the visitors called out kindly or he recognized a familiar voice, he might come forward to the side of the car. Many who sought him out learned to bring offerings to break the ice – typically beer or cigarettes, which Ray was known to enjoy on occasion . A standard practice developed: youth would offer him a cold beer or an unopened pack of cigarettes (to show it wasn’t tampered with, as a sign of goodwill) . In exchange, Ray might chat with them for a short while, even pose for a photograph if asked. Countless Western Pennsylvanians from the mid-20th century have treasured (or notoriously bragged about) Polaroid snapshots of themselves smiling nervously next to the man they called Charlie No-Face.

It’s during this era that Ray earned his nicknames. No one is sure who coined “Charlie No-Face,” but it caught on quickly in Beaver County vernacular . Perhaps the name “Charlie” was chosen arbitrarily (since “Ray No-Face” doesn’t have the same ring), or it might have been a reference to Charlie as a generic everyman name. In any case, Charlie No-Face was how he was known close to home, while farther out in the region people began referring to him as The Green Man. This latter nickname would fuel the ghostly aspects of the legend. Why green? One theory is that the legend picked up embellishments that Ray had been somehow “tinged green” by the electrical accident – an almost radioactive or otherworldly detail that made the story spookier . But there’s also a more gruesome possible origin: Ray’s documentarian Tisha York found that Ray’s nose wound never fully healed and would sometimes get infected, oozing a greenish fluid – which might have given a literal green hue to part of his face . It’s ironic and heartbreaking that an infection could be twisted into supernatural “green skin” in the folklore. Regardless of how it started, the Green Man moniker stuck, especially in stories circulating farther from Beaver County.

As the legend-tripping grew more popular, Ray’s family became increasingly upset – and for good reason. What had begun as occasional friendly visits ballooned into frequent disruptions. Cars would cruise down their rural road at all hours, sometimes dozens of vehicles in a single night, especially in the 1960s when word of “Charlie No-Face” was at its peak . Teenagers, being teenagers, were not always respectful. Some would honk horns or shout taunts, startling Ray if he was in earshot. Others even had the nerve to drive right up to the Robinsons’ home in Koppel and beep, yelling “We want to see Charlie!” from the driveway in the middle of the night . This was more than the family could tolerate. They fiercely protected Ray, chasing away thrill-seekers who trespassed. In one outrageous incident, a carnival sideshow promoter showed up offering money to hire Ray as a “freak” attraction during a local fair – an idea that so infuriated Ray’s nephew that the man was nearly met with a fistfight .

For Ray’s relatives, these constant gawkers felt exploitative and cruel. They hated the demeaning nicknames “Green Man” and “No-Face” being used about someone they loved . Most of all, they worried about Ray’s safety. Kind strangers bearing beer could easily turn into drunks who might harass or harm him. Sadly, not every visitor treated Ray with dignity. There are stories (unconfirmed, but repeated by witnesses) of people picking Ray up in their car and driving him to a bar as a mean prank, or of cruel youths who would suddenly turn off the car lights and speed away, leaving the blind man disoriented on a backroad . Ray himself confided to friends that some people were nasty to him during encounters . On a few occasions, he overindulged in the beers offered to him and got lost, once ending up spending a cold night in the woods and crawling toward the road at daybreak, and another time being found lying in a farm field, drunk and ill . His family would have to scour the area to find him when he didn’t return home.

Yet, amidst the troublesome incidents were also genuine friendships that formed. Many young people came initially out of morbid curiosity, but returned again and again because they found Ray to be good company – a gentle, interesting soul rather than a horror to be feared. One Beaver Falls native, Jim Tripodi, recalled that in the late ’60s he and his high school buddies started visiting Ray just to scare their dates (the boys used “going to see the Green Man” as an excuse to make their girlfriends cling tighter out of fright) . But over time, Tripodi said, they realized “he was just a lonely guy who wanted company”. The teens grew to befriend Raymond, bringing him his favorite cigarettes and chatting about everyday things like the weather . They never mentioned his injuries – and he never brought them up either. In those moments, he wasn’t a monster or an attraction; he was simply Ray, happy to have someone to talk to besides his family. Tripodi and others made a point to treat Ray with dignity, and in return they got to know the person beneath the legend .

These kinder visitors often came to cherish their time with Ray. One local man who frequently stopped to chat with Ray in the ’70s said that meeting the so-called boogeyman and discovering “he’s just a misunderstood guy who likes beer, shooting the breeze, and the Pittsburgh Pirates” completely changed his perspective . Instead of a scare, they got a life lesson in empathy. In fact, Ray’s positivity in the face of hardship left a deep mark on many who met him. Years later, grown men would tear up recalling late nights spent sitting on a porch or in a parked car with Ray, just talking. In those quiet conversations, Ray taught people about looking past appearances, about kindness and strength . As one researcher eloquently put it, he showed so many that it was okay to be different. Far from damaging their youth, meeting Charlie No-Face often became a profound, humanizing experience.

Throughout the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s, Charlie No-Face’s reputation spread far and wide. Visitors from all over the region swapped stories of their encounters. Each time the story was retold, a few new embellishments or errors crept in – a natural game of telephone. By the time those teens grew up and told their children and grandchildren, the lines between fact and fiction had blurred considerably . Some knew him only as a frightful tale rather than a real person. The legend was well on its way to eclipsing the truth.

Myth Overtakes Reality

By the early 1970s, Raymond Robinson’s health and energy were beginning to decline. He was now in his 60s and had spent literally three decades walking that highway at night. Fewer teens encountered him firsthand as the years went on – many of the curious kids of the ’50s and ’60s had grown up or moved away, taking their stories with them . Ray also wasn’t venturing out as often; age and past injuries were catching up, and the traffic on local roads had increased making nighttime walks more perilous. Sometime in the late 1970s (those close to him aren’t sure exactly when), Ray stopped his nocturnal walks altogether . The road between Koppel and New Galilee fell silent; the Green Man, it seemed, had finally retired.

But by then, the urban legend had a life of its own. Those who had seen or met Ray in person continued to tell the tale, and new generations only heard the exaggerated versions. Without the real man around as a tangible reference, Charlie No-Face transformed fully into folklore. What had once been a somewhat contained Beaver Valley legend now exploded into a full-blown ghost story that all of Western Pennsylvania “knew” in one form or another.

Want a quick breakdown of myth vs. reality? This companion article separates spooky legends from the real life of Raymond Robinson.

Folklorists classify the Green Man tale as an example of a localized urban legend – a story rooted in real events but magnified and mutated by retellings, much like the mythologizing of real events seen in Pittsburgh’s labor history, such as the bloody Homestead Strike of 1892. Thomas White, a folklore specialist at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, has studied the Charlie No-Face phenomenon extensively. He notes that every version of the Green Man story involves some grounding in industrial accident or electrical tragedy, reflecting the region’s industrial heritage . In these myths, the Green Man often worked in a power plant or was electrocuted by lightning or a downed wire – directly echoing Ray’s true childhood accident . The detail of green-tinted skin gets explained variously: some say chemical spills turned him green, others that he glows green at night due to the electricity. The ghostly Green Man is always said to haunt out-of-the-way places – fittingly, since Ray walked remote roads. And there’s typically a ritual to summon him, like honking three times or flashing your high beams, which matches how thrill-seekers would try to draw Ray out when he was alive .

One of the most enduring locations tied to the legend is the so-called Green Man’s Tunnel in South Park. This is an abandoned railroad tunnel in South Park Township (south of Pittsburgh) that for decades has been a popular “haunted hangout” for teenagers from the South Hills. Even though Ray Robinson never set foot there – it’s about 40 miles from his home – the South Park tunnel legend insists that’s where the Green Man can be found. The tunnel is graffiti-covered and spooky, and kids would drive through it at night expecting the Green Man’s “shimmering green form” to appear stalking them in the darkness . The truly bold might even turn off their car headlights in the middle of the tunnel and call out “Green Man, show yourself!” then squeal in delight (or terror) at any hint of movement. Over the years, that tunnel accrued additional ghost stories – one about a man who murdered his family with a hatchet there, for instance – layering myth upon myth . But to this day locals still refer to it plainly as Green Man Tunnel, a testament to how strongly Charlie No-Face’s story permeated Pittsburgh folklore .

The abandoned railroad tunnel in South Park Township, known locally as “Green Man’s Tunnel,” became a popular site for thrill-seekers inspired by the Charlie No-Face legend. Teenagers would drive through this graffiti-laden tunnel at night, hoping for a glimpse of the Green Man’s ghostly figure . The real Raymond Robinson never haunted this spot – the tunnel’s eerie reputation stemmed entirely from evolving urban legend.

Throughout the late 20th century, the legend of Charlie No-Face/Green Man persisted and evolved. Without Ray visible on the roads, some storytellers began to imply that he had died and it was his ghost people saw. Others, not realizing the Green Man had been a living person, embellished the story with gory new details (for example, that he glows green because of a chemical accident, or that he’ll attack cars that come looking for him). By the 1980s, Charlie No-Face had become a classic Pittsburgh-area ghost story – a bit of local lore to scare outsiders and newcomers. Kids swapping stories at sleepovers in Allegheny County might not even connect the tale to Beaver County at all; it was just something that happened to a friend’s cousin or some guy my dad heard about. And so, truth was obscured by legend, just as Ray’s family had long feared .

Raymond’s Final Years and Peaceful Passing

While his legend grew ever larger, the real Raymond Robinson lived out his last years quietly. He had stopped walking the highway a few years prior, as maintaining balance and avoiding traffic in the dark became too risky in old age . In the early 1980s, with his health declining, Ray finally agreed to move into a care facility. He became a resident of the Beaver County Geriatric Center (later renamed Friendship Ridge) in Brighton Township . Even there, he was not forgotten – locals who knew the truth would occasionally drop by to visit the man who had become a local legend.

On June 11, 1985, at the age of 74, Raymond Robinson passed away from natural causes . In a poignant coincidence, he died just one week shy of the 66th anniversary of the accident that had defined his life . He was laid to rest in Grandview Cemetery in Beaver Falls, buried in the Robinson family plot on a hill that actually overlooks the site where the old Wallace Run trolley bridge once stood . In an even more touching twist of fate, the grave of young Robert Littell – the boy who had died on that bridge months before Ray’s accident in 1919 – lies only a few feet away from Raymond’s resting place . The two victims of the Harmony Line’s deadly wires, reunited by history, sleep side by side.

Ray’s funeral was a modest affair. To the community in Beaver County, he was not “Charlie No-Face the monster,” but Uncle Ray, the beloved neighbor. Those who had known him in person mourned a kind, brave man who never let his tragic injuries turn his heart bitter. Meanwhile, many Western Pennsylvanians didn’t even realize the Green Man was a real person, let alone that he had died. The legend was by now so detached from reality that local papers felt the need to run human-interest stories to inform the public that Charlie No-Face had been real (and that he was gone). In fact, it wasn’t until some decades later, in the 2000s, that broader awareness sank in about Raymond’s true story. Writers and folklorists began publishing well-researched accounts in newspapers, books, and online to celebrate the life behind the legend and to dispel the wildest rumors.

Legacy of a “Monster” Who Was a Man

Today, more than 100 years after Raymond Robinson’s fateful injury and 40 years after his death, the tale of Charlie No-Face remains firmly embedded in the cultural memory of Pittsburgh and its surrounding communities. The story has proven surprisingly durable – it still gets told around campfires and on hayrides every Halloween, and it continues to send shivers down the spines of new generations. But importantly, efforts have been made to remember Raymond as a person, not just a spooky character. Local historians like Thomas White include the real story of the Green Man in their talks, often astonishing teenagers who had only heard the ghost version that “it was based on a real person” . Folklore enthusiasts have published articles setting the record straight. Even the popular press picked up the story: for instance, a 2024 Pittsburgh TV segment interviewed Ray’s great-niece, Pauline Robinson LaCount, who reminded viewers that “the monster tales are not how he should be remembered” . She emphasized her Uncle Ray’s kindness to everybody, saying he “always tried to be friendly… always caring,” and that perhaps he was kept on this earth for so long to teach others about compassion beyond appearances .

In Beaver County, Charlie No-Face is often spoken of with a sort of local pride now – a unique bit of homegrown folklore. People swap stories of their grandparents meeting him, or how it was “tradition” to drive out to see him back in the day . There are even artifacts of his life that occasionally surface: old photographs taken by those night visitors (some clearly showing Ray with his cane and cardigan on the roadside), and personal anecdotes written down by those who had meaningful encounters. One famous photo shows Ray smiling with a woman who had overcome her fear to put an arm around him; it’s said to be possibly the only time, aside from family, that he ever touched a woman in friendship . Another recollection comes from a man who lost his brother in Vietnam – he credited late-night talks with Ray, who listened with infinite empathy, as helping him cope with his grief . These accounts paint a picture of Raymond’s quiet heroism: through simple human connection, he gave others comfort and perspective.

Culturally, the story has inspired creative works as well. Ray’s life and legend have been the subject of poems, plays, and planned films . A college professor once wrote a poem about Charlie No-Face, and a local playwright featured a character based on him. In the late 2000s, an independent filmmaker named Tisha York researched Ray’s life for years, intending to create a documentary or biopic titled “Route 351” (a nod to the highway he walked) . Although the film itself hasn’t been completed, her research helped illuminate Ray’s personal history and collected many oral histories from people whose lives he touched . Even without a Hollywood movie, Charlie No-Face’s legend has traveled far – he’s mentioned in books of American folklore, on countless websites, and there’s even a Pittsburgh brewery that named a beer after the Green Man in playful homage.

Perhaps the most fitting tribute to Raymond Robinson is the simplest one. At his gravesite in Beaver Falls, one might occasionally find fresh flowers laid on his headstone . Whether it’s a family member, a fan of folklore paying respects, or someone whose grandparents told them “if you ever find his grave, put flowers for me,” it shows that he is not forgotten. The flowers acknowledge both the man and the myth: a life of suffering and strength, and a legend that grew from it.

In the end, the tale of Charlie No-Face is a uniquely Pittsburgh story of tragedy, resilience, and the power of storytelling. It’s about how a community, over generations, can transform a painful reality into a piece of communal lore – for better or worse. Raymond Robinson endured one of the worst accidents imaginable, yet lived with grace and positivity. He never sought fame or fright, yet became a figure of fear and fascination to thousands. The Green Man will undoubtedly continue to roam the imaginations of Western Pennsylvanians, but now you know the truth behind the tale. The next time you hear someone spin the yarn of the glowing man with no face, you can tell them: “Charlie No-Face was real, and his true story is more touching – and more interesting – than any ghost story.”