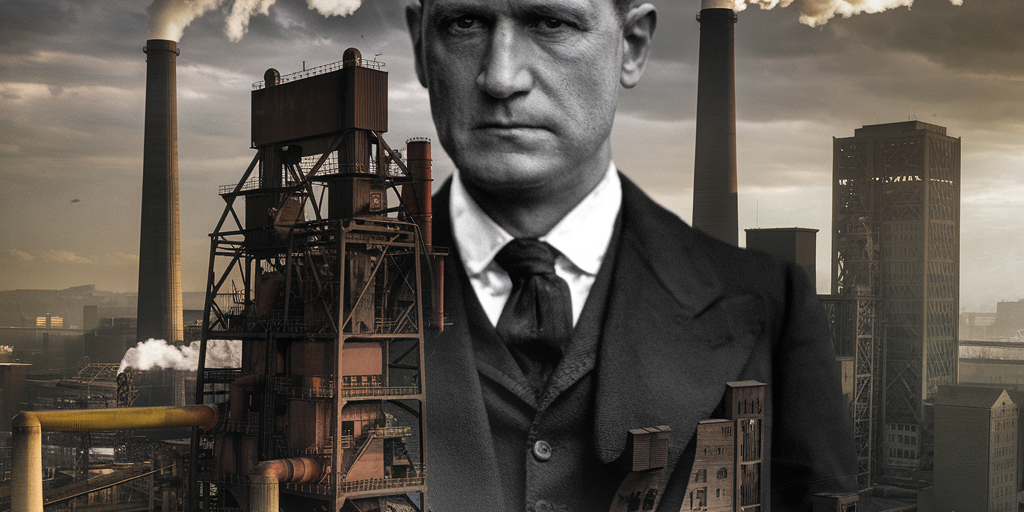

Introduction: The Ruthless Mogul Who Built Pittsburgh’s Empire

In the pantheon of American industrial titans, few figures spark as much debate as Henry Clay Frick. A brilliant capitalist and ruthless businessman, Frick helped build Pittsburgh’s steel empire, shaped the Gilded Age, and amassed one of the country’s most impressive art collections. Yet, his name remains shadowed by labor conflicts, deadly disasters, and controversy that still echoes through Pittsburgh’s history.

Born poor and dying fabulously wealthy, Frick’s life is a tale of ambition, power, and the high cost of empire-building. Loved by few but respected by all, he embodied the harsh reality of American industrialization.

Early Life and Rise to Wealth

Henry Clay Frick was born on December 19, 1849, in West Overton, Pennsylvania, a small rural community in Westmoreland County. His family’s modest means instilled in him an early drive for wealth and influence. Frick’s maternal grandfather owned a whiskey distillery, exposing young Henry to the hard-nosed business world.

Frick’s real fortune began with coke — the fuel essential for steel production. At just 21 years old, he co-founded Frick & Company, specializing in producing coke from coal mined in the region’s vast reserves. By 1880, Frick controlled 80% of the Connellsville coke fields, earning him the nickname “The Coke King.”

This success caught the attention of Andrew Carnegie, Pittsburgh’s rising steel magnate. The two men became partners, with Frick’s coke feeding Carnegie’s steel mills — a relationship that would define an era and make both men immensely wealthy.

The Carnegie Steel Years: Power, Expansion, and Ruthlessness

In 1882, Frick officially joined Carnegie as chairman of the newly formed Carnegie Steel Company, overseeing daily operations. Under his leadership, the company became the largest and most profitable steel company in the world, supplying materials for America’s railroads, skyscrapers, and infrastructure.

Frick was known for his efficiency, discipline, and brutal cost-cutting. He opposed unions, reduced wages, and forced 12-hour workdays, seeing organized labor as a direct threat to capitalism. These views would culminate in one of the most infamous events in American labor history: The Homestead Strike of 1892.

The Homestead Strike: Bloodshed on the Monongahela

The Homestead Steel Works, outside Pittsburgh, became the epicenter of Frick’s legacy — and his most lasting stain. Faced with growing union power from the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers, Frick sought to break the union entirely.

In 1892, while Carnegie conveniently vacationed in Scotland, Frick locked out workers and hired 300 Pinkerton detectives to seize the mill. A violent battle erupted on July 6, 1892 along the banks of the Monongahela River. Gunfire was exchanged, leading to the deaths of seven workers and three Pinkertons.

The nation watched in horror. Though Frick technically won — the union was crushed — his reputation never recovered. To many, he was the “most hated man in America”, a symbol of capitalist oppression.

Anarchist Attack: Surviving an Assassination Attempt

Just weeks after the Homestead bloodshed, Frick faced personal violence. On July 23, 1892, anarchist Alexander Berkman entered Frick’s Pittsburgh office and shot him twice at point-blank range before stabbing him.

Incredibly, Frick survived the attack — and even returned to work within days. The assassination attempt, while condemning Berkman, also complicated public perception of Frick. He was tough, fearless, and utterly unrepentant.

Fallout with Carnegie and the Formation of U.S. Steel

Despite their partnership, Frick and Carnegie’s relationship soured. Frick despised Carnegie’s public persona as a philanthropist while privately urging aggressive tactics. The two men’s bitter feud eventually led to Frick’s ousting from Carnegie Steel in 1899.

Yet Frick remained a major player. When J.P. Morgan orchestrated the formation of U.S. Steel — the world’s first billion-dollar corporation — Frick secured a seat on the board. By the dawn of the 20th century, he was among America’s richest men.

Frick’s Impact on Pittsburgh’s Landscape

While Frick’s business practices were ruthless, his impact on Pittsburgh’s physical and cultural landscape is undeniable:

- Frick Park: Upon his death, Frick donated 151 acres to create what became Pittsburgh’s largest municipal park.

- The Frick Pittsburgh: His mansion, Clayton, in the East End, remains a museum complex showcasing his life and art collection.

- Uniontown and Connellsville: Entire towns and industries rose and fell based on Frick’s business decisions.

Frick’s influence extended beyond steel. He invested in railroads, banking, and even served as a director of the Pennsylvania Railroad.

The Art Collector: A Softer Side?

In his later years, Frick turned his attention to the arts. Like many Gilded Age tycoons, he sought cultural immortality. He amassed one of the world’s finest private art collections, featuring works by Vermeer, Rembrandt, Goya, and Turner.

While most of his collection was eventually moved to The Frick Collection in New York City, some pieces remain in Pittsburgh. To this day, his art holdings are considered among the most significant assembled by an American.

Yet even his philanthropy was met with suspicion — many viewed it as an attempt to whitewash his legacy.

Death and Complicated Legacy

Frick died on December 2, 1919, in New York City, just shy of his 70th birthday. His will contained generous donations — but he left strict stipulations to keep his art intact, reflecting his need for control, even in death.

To Pittsburgh, Henry Clay Frick remains a paradox:

- A self-made titan who helped build a city.

- A ruthless capitalist whose actions caused suffering.

- A patron of the arts who left behind cultural treasures.

Today, his name graces parks, museums, and buildings — reminders of both his brilliance and brutality.

Conclusion: Pittsburgh’s Dark Prince of Industry

Henry Clay Frick’s story is one of ambition without apology. He didn’t seek adoration. Instead, he pursued power, wealth, and influence — no matter the cost.

His impact on Pittsburgh is indelible. The city’s rise as an industrial powerhouse owes much to Frick’s relentless drive. But so too does the story of American labor’s struggle for dignity and rights — forged in the crucible of places like Homestead.

Frick was a man of contradictions: ruthless yet refined, feared but respected. In many ways, he was the embodiment of the Gilded Age — where fortunes were made, blood was spilled, and the foundations of modern America were laid.