Pittsburgh’s underworld has a rich and turbulent history, from the wild days of Prohibition-era bootleggers to the iron grip of mid-century Mafia bosses, and from infamous outlaws who terrorized the region to modern high-stakes heists and corruption scandals. Each era left its mark on the Steel City’s lore and shaped law enforcement responses in lasting ways. What follows is a historical journey through Pittsburgh’s most notorious gangsters and crime sagas – an engaging narrative of speakeasy shootouts, Mafia meetings, bank robberies, and headline-grabbing crimes that have become part of local legend.

Prohibition Era (1920s–30s): Bootleggers and Speakeasy Wars

During Prohibition, Pittsburgh became a battleground for bootleggers and gangsters as illegal liquor flowed freely despite the 18th Amendment’s ban (1920–1933). The city’s Italian underworld split into factions – Sicilian gangs versus Neapolitan gangs – vying for control of speakeasies and moonshine rackets  . Violence exploded: between 1926 and 1933, over 200 gangland murders were recorded in Allegheny County as rival mobs fought over territory . In the city’s Hill District, a stout racketeer named Luigi “Big Gorilla” Lamendola built a moonshine monopoly through brutality and intimidation. Lamendola reportedly had underworld connections stretching to Al Capone’s Chicago, and he carried a sword-cane for protection – a testament to the constant peril of the bootleg trade. His reign ended in a hail of gunfire on May 19, 1927, when Lamendola was assassinated outside his Chatham Street restaurant, in what newspapers first claimed was Pittsburgh’s first machine-gun murder (later determined to be a shotgun blast)  . The sensational killing of the “Big Gorilla” underscored how dangerous the life of a booze baron had become in the Steel City.

A shadowy alley in Pittsburgh’s Hill District, where illegal stills and speakeasies thrived during Prohibition.

As Prohibition wore on, gangland rivalries intensified. Bombings of rival distilleries, drive-by shootings, and even public assassinations were not uncommon. One powerful early Mafia boss, Stefano Monastero, allegedly ordered bombings of competing stills and had his rival Luigi “Big Gorilla” Lamendola eliminated in 1927 . But Monastero’s own luck ran out; he and his brother Sam were gunned down in front of a Pittsburgh hospital in August 1929 , victims of the ceaseless power struggles. By the early 1930s, a formidable organization known as the Volpe brothers had risen to dominance. Led by John Volpe and his siblings, the Volpe gang (sometimes called the “House of Volpe”) controlled a large share of the illicit liquor supply in Pittsburgh by 1932 . The Volpes grew rich and bold – John Volpe drove a custom bulletproof Cadillac and reputedly even received condolences from Al Capone when one Volpe brother died in a car crash . Their headquarters was the Rome Coffee Shop at 704 Wylie Avenue in the Hill District, a nondescript café that concealed a hub of bootlegging and numbers rackets  .

The Volpe brothers’ success ultimately made them targets. In summer 1932, Pittsburgh Mafia boss John Bazzano – who had once allied with the Volpes – grew aggravated as the Volpe faction encroached on new turf . On July 29, 1932, Bazzano sent a hit squad to the Rome Coffee Shop in broad daylight. As John Volpe stepped outside for a midday stroll, gunmen led by a former Volpe bodyguard opened fire. In the ensuing massacre, John Volpe and two of his brothers (James and Arthur) were slain in classic gangland style . The daring triple murder shocked the city. But the fallout did not end there: the Volpe family appealed to higher powers in organized crime, and the Mafia’s national Commission did not approve of Bazzano’s unsanctioned hit. In retribution, Bazzano himself was found dead in a Brooklyn sack just days later – strangled and stabbed for overstepping his bounds . The dramatic purge of both the Volpe gang leaders and Bazzano effectively ended the worst of the bootleg wars in Pittsburgh. By the time Prohibition was repealed in 1933, the bloody bootleg era had firmly established an Italian-American Mafia presence in the city and left a legacy of corruption and violence that would echo for decades.

The daylight assassination of John Volpe and his brothers shocked Pittsburgh in 1932 — a classic mob hit that marked the end of the Volpe gang’s reign.

Mid-20th Century Organized Crime: The Pittsburgh Mafia’s Golden Era

With Prohibition over, Pittsburgh’s underworld transitioned from bootlegging to other rackets – and the LaRocca crime family rose to prominence. Formed from the remnants of the earlier factions, the Pittsburgh Mafia consolidated under a series of powerful bosses. Frank Amato led in the 1940s–50s, expanding gambling operations and forging ties with New York mob families . But it was his successor, Sebastian “Big John” LaRocca, who truly ushered in the family’s golden era. LaRocca, a Sicilian immigrant with a deceptively ordinary business selling beer equipment in Oakland, became boss in 1956 and ruled for nearly 30 years until his death in 1984 . Under LaRocca, the Pittsburgh Mafia thrived by keeping a low profile and making friends in high places. Federal agents learned that LaRocca had corrupt city officials, police, and politicians on his payroll through bribery, ensuring the family’s gambling and racketeering enterprises faced minimal interference . The crime family also entrenched itself in organized labor; they effectively controlled Laborers Local 1058, drawing on Pittsburgh’s long history of labor struggles to their advantage.

In the 1950s, LaRocca’s influence extended far beyond Pittsburgh. He attended the infamous 1957 Apalachin conference, a nationwide mob summit in upstate New York, alongside his capos Gabriel “Kelly” Mannarino and Michael Genovese . When state troopers raided that meeting, LaRocca managed a swift escape into the woods while many other bosses were caught  – a testament to his cunning. Back home, LaRocca cultivated alliances with titans of the American Mafia like New York’s Carlo Gambino and Philadelphia’s Angelo Bruno , reinforcing Pittsburgh’s connections to the national crime network. He even teamed up with Tampa boss Santo Trafficante Jr. to invest in the Sans Souci casino in pre-revolution Havana, Cuba . For a time, the money poured in from casinos and illegal lotteries. One Pittsburgh gambling kingpin, Tony Grosso, ran a huge numbers racket parallel to the Mafia; by the 1960s, Grosso’s underground lottery employed an estimated 5,000 people and grossed $30 million annually . (Such was the demand for illegal betting that even non-Italian racketeers like Gus Greenlee and Grosso became local legends.) LaRocca largely tolerated these operations as long as he received a cut or cooperation. With bribes and political clout, the Mafia’s grip on Pittsburgh in the mid-20th century was so tight that newspapers only whispered of organized crime, and many cops looked the other way.

LaRocca’s reign was not without challenges. In the 1960s, a mob dispute flared with the Cleveland syndicate over territory in Youngstown, Ohio – a conflict Pittsburgh ultimately won, extending its influence westward . But overall, LaRocca kept the peace and prosperity. When “Big John” died of natural causes in 1984, his longtime consigliere Michael Genovese (no relation to the NY Genoveses) assumed the mantle  . By then, however, the golden age was fading and law enforcement was closing in. The late 1980s brought aggressive FBI investigations that would finally crack Pittsburgh’s Mafia. In March 1990, an extensive federal indictment charged Genovese’s underboss Charles “Chucky” Porter and lieutenant Louis Raucci Sr. with a litany of crimes – from drug trafficking and extortion to gambling and even murder conspiracy . The evidence was damning, and both Porter and Raucci were convicted. Facing a long prison term, Chucky Porter broke the Mafia’s code of silence and turned state’s witness, spilling secrets that helped convict many top Pittsburgh mobsters . This betrayal was a devastating blow. By 1992, authorities reported that only a few aging members and associates remained active . The once-powerful Pittsburgh Mafia had been reduced to a shadow of its former self. Boss Michael Genovese, wary after seeing his underboss flip, kept a low profile on his rural estate and avoided further indictments until he died quietly in 2006. A couple of old-timers—like John Bazzano Jr. (son of the 1930s boss) and soldier Thomas “Sonny” Ciancutti—nominally held the reins into the 2000s, but their activity was minimal  . By the 21st century, Pittsburgh’s LaRocca crime family had essentially disintegrated, its reign ended by time, internal betrayal, and relentless law enforcement pressure. Yet its legacy of corruption and lore of hidden gambling fortunes still linger in Pittsburgh’s history.

Infamous Individual Criminals: Legends of Pittsburgh’s Underworld

Not all of Pittsburgh’s notorious criminals were part of organized crime – some operated outside the Mafia’s code, carving their own violent path through history. These are the infamous outlaws, bank robbers, and murderers whose crime sprees struck fear in Western Pennsylvania and captured national headlines.

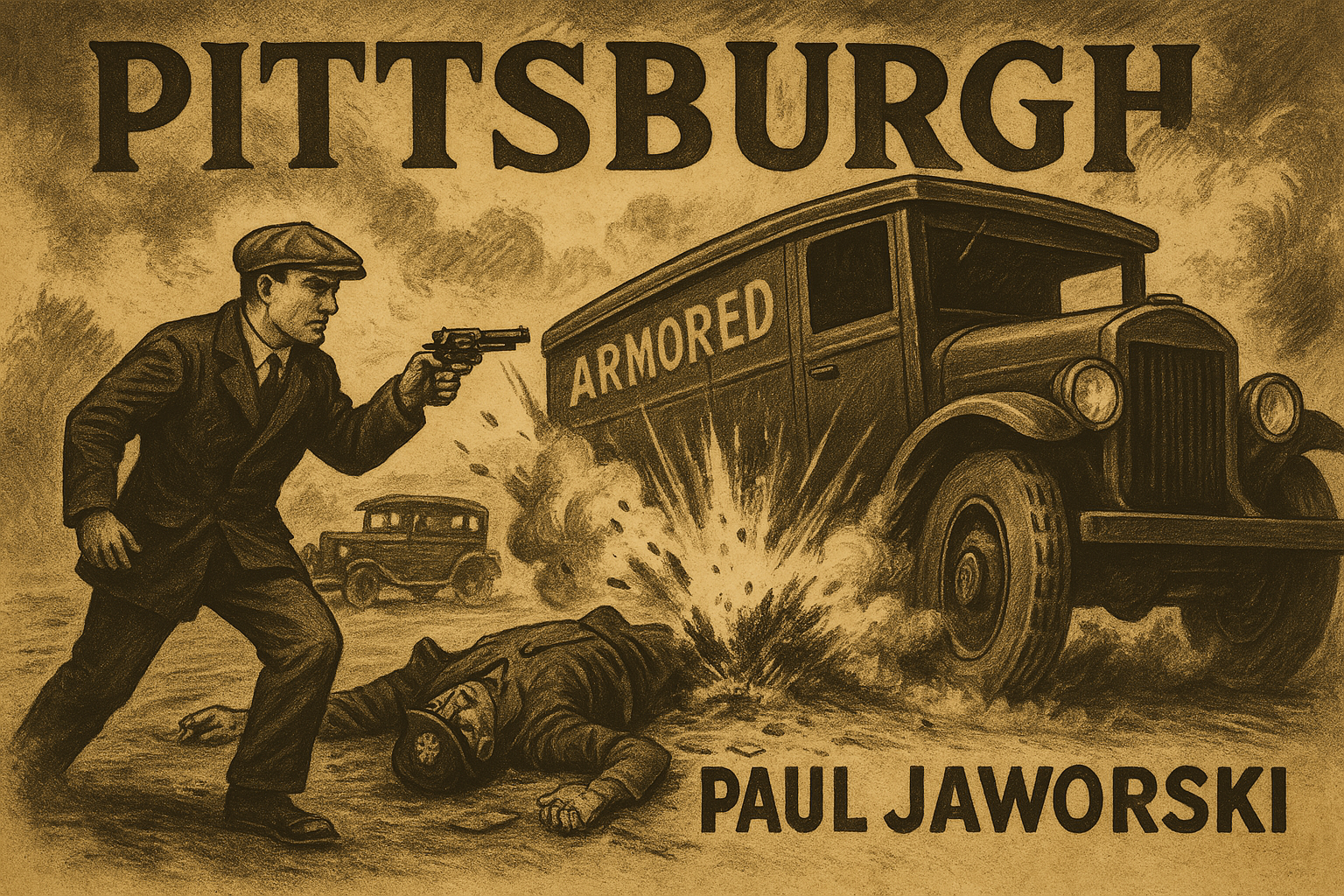

One early figure was Paul Jaworski, leader of the “Flathead Gang” in the 1920s. Jaworski was a Polish-American bandit who advanced the art of the robbery with chilling audacity. On March 11, 1927, he and his gang committed the first-ever armored car robbery in U.S. history – right outside Pittsburgh . They buried explosives under a road in Bethel Park and detonated them as a Brinks armored truck passed, blowing open the vehicle. Amid flying rubble, the Flatheads seized over $104,000 in cash (a fortune at the time) . This unprecedented heist, executed with military precision, stunned law enforcement and made Jaworski a wanted man across multiple states. Jaworski’s gang pulled off other bold robberies (including a Detroit newspaper payroll) and were implicated in numerous killings. Jaworski himself was said to have murdered up to 26 people during his criminal career . After a dramatic capture in 1928 – he was shot by police but survived – Jaworski faced justice. In January 1929, he was executed by electric chair in Pennsylvania for a murder during one of his robberies . The short, violent life of Paul Jaworski became the stuff of Pittsburgh legend: a bandit who blasted his way into the record books and paid the ultimate price, contributing to the region’s reputation as a proving ground for outlaws.

Fast-forward a few decades and a different kind of terror gripped Pittsburgh. In 1969, Stanley Barton Hoss Jr. emerged as one of the region’s most notorious criminals – a desperado whose crime spree shook the nation. Hoss was a small-time thief from the suburbs who turned into a monster of headline news. On September 11, 1969, while serving time for assault, the 26-year-old Hoss pulled off a brazen escape from the Allegheny County Workhouse: he sawed through jail bars and rappelled down a wall on knotted bedsheets . Eight days later, Hoss’s newfound freedom turned bloody. On September 19, 1969, Verona Police Officer Joseph Zanella, a young father of two, pulled over a car matching a stolen vehicle report – behind the wheel was Hoss. Hoss shot the officer point-blank in the heart, killing him on a neighborhood street . The murder of a cop put the city on immediate high alert. Hoss went on the run, and within days he struck again with even more shocking cruelty: on September 22, he kidnapped 21-year-old Linda Peugeot and her 2-year-old daughter Lori from a Maryland parking lot . The fugitives’ car was later found, but mother and child had vanished. A multi-state manhunt ensued; even FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover called in Army reservists and helicopters to assist in searching for the heavily armed Hoss . After two harrowing weeks, Hoss was finally captured on October 4, 1969 in Waterloo, Iowa, driving his victim’s stolen car . Under interrogation, the remorseless Hoss confessed to murdering Linda Peugeot and smothering little Lori – though despite exhaustive searches, the bodies were never recovered . Convicted of Officer Zanella’s killing, Hoss initially received a death sentence that was later commuted to life in prison . But even behind bars, his violence didn’t end: in 1973, Hoss and two other inmates beat a prison guard to death in a racially charged killing . Finally, in 1978, Stanley Hoss met a grim end by his own hand, hanging himself in his cell . Hoss’s eight-month saga of escape, cop-killing, kidnapping, and prison mayhem made him one of western Pennsylvania’s most feared criminals – a boogeyman whose name still sends a shiver through those who remember the autumn of 1969.

Only a decade later, Pittsburgh was rocked by another murderous rampage, this one known infamously as the “Kill for Thrill” spree. Around the turn of the new decade – late December 1979 into January 1980 – two young men, John Lesko (21) and Michael Travaglia (20), embarked on a week-long orgy of violence “just for the thrill” of it. Their crime spree began on December 27, 1979, when they lured Peter Levato (or “Lovato”), a 49-year-old North Side man, into their car in downtown Pittsburgh. They tortured him and fatally shot him near the Loyalhanna Dam in Westmoreland County . Four days later, on New Year’s Eve, the pair picked up an innocent hitchhiker – 26-year-old Marlene Newcomer – and murdered her, dumping her body in a Pittsburgh parking garage . As the region grew unnerved by seemingly random killings, Lesko and Travaglia struck again on January 1, 1980. They kidnapped William Nicholls, a church organist from Mt. Lebanon, and subjected him to horrific abuse: the men tied Nicholls up, drove him to a rural lake, weighed him down with rocks and drowned him in the icy water . By now a tri-county manhunt was underway for the unknown killers. The duo’s final crime was perhaps the most brazen – and ultimately led to their capture. On January 3, 1980, Apollo (PA) police officer Leonard Miller, just 21 and a recent police academy graduate, noticed Lesko and Travaglia’s vehicle speeding. The killers dared the young officer into a pursuit, then ambushed him on a bridge: they crashed, pretended to surrender, and then shot Officer Miller to death on the Apollo Bridge . Within days, police arrested Lesko and Travaglia, recovering weapons and evidence of their crimes. The “Kill for Thrill” killers were convicted in 1981 – receiving multiple life terms and, for Miller’s murder, sentences of death. Travaglia died in prison of natural causes in 2017, but John Lesko remains on Pennsylvania’s death row over 40 years later, his execution delayed by numerous appeals  . The wanton brutality of their spree – four innocent lives taken for no reason other than sadistic excitement – left an indelible mark on Pittsburgh’s crime history. It also spurred changes: Officer Miller’s hometown later named a new bridge in his honor , and the case became a lasting cautionary tale about the random dangers that can lurk even in everyday encounters.

From the early 20th-century banditry of Paul Jaworski to the senseless carnage of Lesko and Travaglia, Pittsburgh’s infamous individual criminals have ranged widely – bank robbers, cop killers, kidnappers, and more. Each saga brought public outrage and grief, but also steeled the resolve of law enforcement. The FBI’s aggressive pursuit of Hoss across state lines in 1969, for example, set precedents for multi-agency manhunts. And the “Kill for Thrill” case influenced police training on handling roadside stops and hitchhiker dangers. These dark chapters are as much a part of Pittsburgh’s history as its steel mills and sports teams – grim reminders that even a tight-knit community forged in the Steel City’s industrial heyday could be stalked by predators in its midst.

Paul Jaworski and the Flathead Gang executed the nation’s first armored car robbery outside Pittsburgh in 1927, detonating explosives and escaping with over $100,000.

Modern-Day Crime: Heists, Scandals, and the Last Echoes of the Mob

In recent decades, Pittsburgh’s underworld has continued to evolve. Traditional organized crime all but withered by the 1990s – the Mafia’s old guard was dying off, and the FBI had largely shattered its infrastructure. After mob boss Michael Genovese’s death in 2006, the LaRocca family effectively ceased to exist as an organized force, with the last reputed don, Sonny Ciancutti, passing away in 2021. Yet the city remained the stage for new kinds of headline-grabbing crimes, from big-money heists to public corruption scandals, proving that the legacy of law-breaking lives on in different forms.

One of the most notorious modern cases is the great Pittsburgh armored car heist of 1982 – a crime as dramatic as any gangster caper, and one that remains unsolved to this day. It unfolded on St. Patrick’s Day 1982 at the Purolator Armored, Inc. depot in suburban Brentwood. In a scene seemingly ripped from a movie, two men slipped into the depot just after an armored truck left. Posing as FBI agents with a bogus “robbery tip,” they fooled a lone guard, then swiftly overpowered him, snatching his shotgun . The impostors handcuffed the guard and taped his eyes shut, then coolly radioed for a getaway van. In a matter of minutes, they loaded about 225 kilograms of cash – roughly $2.5 million – into their vehicle and vanished . Astonishingly, the thieves left behind an additional $55 million sitting in the vault, taking only what they could carry . It was the largest heist in Pittsburgh history at the time, and its precision execution baffled investigators. No suspects were immediately identified, and years passed with little progress. At a 1990 trial unrelated to the case, an informant claimed that a Pittsburgh mob associate named Eugene “Geno” Chiarelli had masterminded the Purolator robbery . However, that allegation was never substantiated – perhaps just underworld gossip. Four decades later, the 1982 Brentwood depot theft endures as a legendary cold case: the money was never recovered, and the culprits never brought to justice . It’s a tale often whispered about in Pittsburgh’s oldest bars – did the Mafia secretly pull one last score? Did an inside man orchestrate it? The mystery only enhances its infamy.

More recently, Pittsburgh saw another dramatic armored car caper – this time solved swiftly, but no less shocking. In February 2012, Kenneth J. Konias Jr., a 22-year-old armored truck guard from the suburbs, decided to stage his own one-man heist. Konias and a fellow guard, Michael Haines, were on their route collecting cash deposits, including a stop at the Rivers Casino on the North Shore . After finishing the rounds, as they parked under the 31st Street Bridge, Konias made his move. He shot his partner Haines in the back of the head at point-blank range inside the truck, killing him instantly in cold blood  . Konias then filled bag after bag with cash – over $2 million worth – and fled the scene, leaving the armored truck (and his murdered colleague) abandoned under the bridge  . Before disappearing, he called a friend and confessed, saying he had enough money to “live the rest of their lives without working” . The ensuing manhunt riveted Pittsburgh for weeks. Detectives tracked Konias’s movements through video surveillance: he returned to the company garage, ditched his bloody uniform, and drove off in his personal vehicle  . It was clear Konias had planned the crime meticulously – even researching places to flee. Indeed, about two months later, in April 2012, FBI agents caught up with him hiding out in Pompano Beach, Florida, with hundreds of thousands of dollars of the loot still in his possession. He was arrested without incident. In court, the rogue guard who betrayed his partner showed little remorse. Konias eventually pleaded guilty and was sentenced to decades in prison for murder, robbery, and theft. The 2012 Garda armored car heist remains one of Pittsburgh’s most brazen modern crimes – notable not only for the staggering sum stolen, but for the tragic betrayal and violence at its core  . It underscored that even as organized crime’s influence waned, big-time criminal schemes were very much alive – now often perpetrated by lone wolves rather than Mafia crews.

Pittsburgh has also confronted corruption within its own halls of power in recent times, proving that crime stories here aren’t limited to the streets. A high-profile example came in 2013, when the city’s Police Bureau was rocked by scandal. Nathan E. Harper, Pittsburgh’s police chief since 2006, was indicted on federal charges for a years-long embezzlement and tax-evasion scheme. Harper had secretly diverted thousands of dollars from city police accounts into slush funds and personal spending – essentially stealing checks meant for the department and using them via off-the-books debit cards . He also failed to pay taxes on his illicit gains. Caught by an FBI public-corruption task force, Harper pleaded guilty and, in early 2014, was sentenced to 18 months in federal prison for conspiracy and tax crimes  . It was a stunning fall from grace for the city’s top cop, and it reminded Pittsburgh that graft can lurk in any corner, even the chief’s office. The case led to reforms in how the police handle funds and reinforced a commitment to rooting out corruption in government. Similarly, other local officials and judges have faced bribery and fraud charges over the years, reflecting a broader theme: the fight against wrongdoing continues not just against gangsters and robbers, but against abuses of public trust.

The legacy of Pittsburgh’s crime history is complex and enduring. The Prohibition era left behind tales of infamous bootleggers and gang wars that still fascinate historians and residents alike – one can stroll through the Hill District and imagine the speakeasies and gun battles that once raged there. The mid-century Mafia era, for all its illegality, ingrained itself in the city’s fabric through political corruption and even charitable acts by mob-connected figures (some remember that certain Mafia bosses quietly donated to churches or helped neighbors, further blurring the lines between villain and folk hero). The downfall of the Pittsburgh Mob in the 1990s was a landmark in law enforcement triumph, closing the chapter on one of the original 24 Cosa Nostra families in America . Meanwhile, the exploits of independent criminals like Stanley Hoss and the “Kill for Thrill” killers became cautionary tales – their names are taught in local criminal justice courses as case studies in profiling and manhunt strategy. Modern heists and scandals continue to test the region’s vigilance but also showcase Pittsburgh’s resilience: each time, the community and authorities respond, adapt, and learn. From the cobblestone alleys of the 1920s to the digital surveillance age of the 2020s, Pittsburgh’s dance with organized and disorganized crime has been a dramatic saga. It’s a story of notorious figures and notorious deeds – whiskey smugglers, mob bosses, bank robbers, thrill-killers, and corrupt officials – all woven into the larger narrative of a city that has seen it all. And through it, Pittsburgh endures, wiser from the past and ever determined to write a safer future.

Go Deeper Into Pittsburgh’s Criminal Underworld

If you found this overview gripping, wait until you explore the full scope of the city’s criminal history. Our dedicated Pittsburgh Mafia & Crime History section dives even further into the brutal power struggles, iconic heists, mob hideouts, and the rise of families like LaRocca and Bazzano.

Don’t just read the headlines—follow the trail through Pittsburgh’s darkest alleys, political backrooms, and blood-soaked history.

Enter the Crime History Hub →