Introduction: Pittsburgh’s Rivers — Highways of Industry

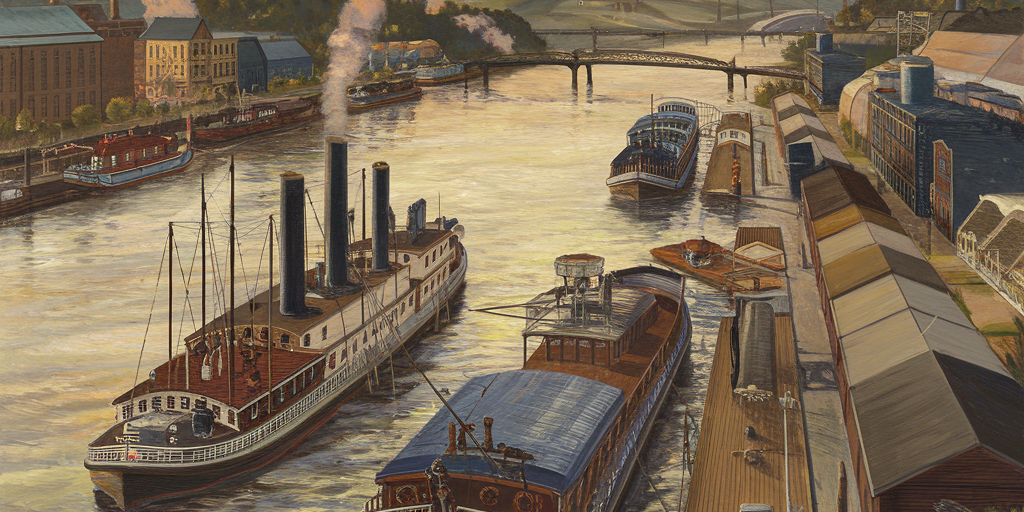

Before railroads crisscrossed the land or highways tied America together, Pittsburgh’s three rivers — the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio — served as vital arteries of commerce, transportation, and industry. Riverboats and barges turned the city into a bustling inland port, fueling its rise as the “Gateway to the West” and later, the Steel Capital of the World.

This is the story of Pittsburgh’s riverboats and the shipping industry — a tale of steamboats, industrial might, and the river highways that built a city.

Early Days: The Birth of Pittsburgh’s River Trade

Pittsburgh’s shipping story begins in the late 1700s and early 1800s when the Ohio River opened westward expansion. Traders and settlers loaded flatboats and keelboats with goods, floating downstream toward Cincinnati, Louisville, and eventually New Orleans.

Key Early Milestones:

- 1780s-1800s: Pittsburgh emerges as a key shipping point for fur, timber, whiskey, and iron goods.

- 1811: The New Orleans, the first steamboat built west of the Alleghenies, launched from Pittsburgh, proving the viability of upstream steam travel.

The city’s location at the confluence of three rivers made it a natural shipping hub, connecting Eastern markets to the frontier and the Mississippi River system.

The Steamboat Era: Pittsburgh’s Rise as an Inland Port

The steamboat revolution of the 19th century transformed Pittsburgh’s economy. By the mid-1800s, Pittsburgh was known as the “Queen of the Western Rivers” for its steamboat production and bustling river traffic.

What Pittsburgh Shipped:

- Coal: Western Pennsylvania coal fueled steam engines, factories, and homes downriver.

- Iron and Steel Products: Beams, rails, nails, and heavy machinery flowed south to build America.

- Glass, Oil, and Lumber: Essential goods for a growing nation.

Pittsburgh’s shipyards produced hundreds of steamboats, supporting local industries and river commerce.

The Riverboat Captains and Crews: Life on the Water

Riverboat captains became local legends — navigating treacherous waters, floods, and shifting sandbars. Crews faced tough, dangerous work as they moved cargo day and night.

Pittsburgh river culture shaped local folklore, music, and labor traditions, creating a working-class heritage that defined much of the region.

Industrial Powerhouse: The Barge Boom of the 20th Century

By the early 1900s, steamboats gave way to tugboats and barges, but Pittsburgh’s rivers were busier than ever:

Why Barges Mattered:

- Heavy Cargo: Barges hauled coal, coke, steel, and chemicals — far heavier loads than trains could manage.

- Efficient Transport: Moving freight by water was cheap and efficient, critical for steel production.

- River Engineering: The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built locks and dams, stabilizing river levels and improving navigation.

By the 1940s, Pittsburgh was one of the largest inland ports in America — vital to the nation’s industrial might during World War II.

The Decline and Modern Revival of River Commerce

The post-war era saw river traffic decline as steel production fell and trucking grew. Yet, Pittsburgh’s rivers never lost their industrial role.

Today, barges still move millions of tons of cargo annually, mostly bulk commodities like coal, sand, gravel, and chemicals.

Modern River Industry Highlights:

- Pittsburgh remains a key player in the Inland Waterways System.

- New industries, like recycling and energy transport, now rely on river shipping.

Meanwhile, riverboat cruises and recreation have revived Pittsburgh’s river heritage, drawing tourists and locals alike.

Conclusion: The Rivers That Built a City

Pittsburgh’s rivers were far more than scenic landmarks — they were the lifeblood of a city. Riverboats, steamboats, and barges powered the industries that made Pittsburgh famous, shaping its economy, culture, and identity.

Today, echoes of that river heritage live on in every barge that passes and every riverfront park that lines the banks. Pittsburgh’s rivers — once highways of industry — remain at the heart of the city’s story.